In the nineteenth century, the cultural historian Jacob Burckhardt famously characterized the Renaissance as a revival, after a full millennium, of the non-Christian values held by the ancient Greeks and Romans. This was not new, as contemporaries of the Renaissance such as Giorgio Vasari had themselves used “rebirth” as the metaphor of the culture of their time. Vasari (d. 1574) all but dismissed the value of the arts between the rise of a Christian culture in Europe after the conversion of Constantine and the rediscovery of classical art in his own time. But Burckhardt (d. 1897) canonized this interpretation for a modern audience. Henceforth the period of Christian art and culture that flowered for a thousand years was dismissed as the “middle ages” when traditional Christianity obscured the worldly potential of human greatness.

This view is no longer held in its purest form by historians, many of whom have today come to discover the riches of medieval art and culture. But like all great ideas it has cast a lasting shadow over our understanding of the past.

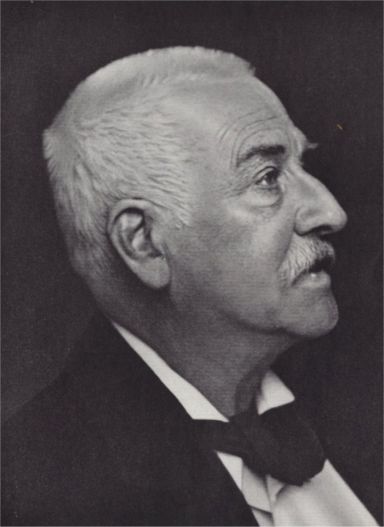

For Burckhardt,

Jacob Burckhardt

the Renaissance (for the first time a distinct period in history) became the moment of cultural liberation, the breakthrough into the modern age of humanism, individualism, and secularism. Himself an agnostic (he started his life as a divinity student but ended it as a lover of classical paganism, like his more forward thinking atheistic friend Friedrich Nietzsche), he hailed the Renaissance as the moment when western civilization broke from its Christian foundation to establish an entirely new culture. And in this, I believe, he is correct, though the break that occurred was not as definitive as he claimed: Much of the medieval world persisted beyond the Renaissance, and there was much in the Renaissance that had occurred during the centuries that preceded it. In any case, he realized that something profound had changed in the values of the west. Christendom’s longing for paradise had begun to give way to the modern world’s efforts to build utopia.

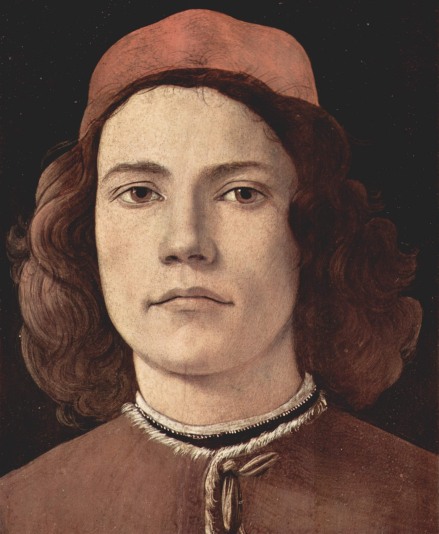

At the heart of this breakthrough was the Renaissance’s reflection on the human condition. Traditional Christianity, as I have noted in earlier posts, contained within it an exalted view of the human being, made in God’s image and made for a relationship of immediate and eternal communion with God. In eastern Christendom Orthodox Christianity had maintained this anthropological optimism about man, but in the centuries that followed the Great Schism of 1054 a more pessimistic view of man had been established in the west. By the time Petrarch appeared in fourteenth-century Italy, this pessimism was great indeed. Soon it would be challenged directly by leading Renaissance humanists such as Giannozzo Manetti (d. 1459). His On the Dignity of Man boldly confronted one of the middle ages most widely published and influential anthropological treatises, Pope Innocent III’s The Misery of the Human Condition. Even more famously, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (d. 1494) issued his own On the Dignity of Man as a corrective to the pessimistic anthropology that had come to choke the culture of western Christendom.

Mirandola

Burckhardt himself regarded the “rediscovery” of human dignity to be the central achievement of the Renaissance, which alone was sufficient “to fill us with everlasting thankfulness.” He actually paraphrased Mirandola’s treatise as the conclusion to his study of Renaissance anthropology.

The statement is remarkable. The human being is no longer the plaything of the passions, no longer enslaved to the “evil desire” identified by Augustine as the Achilles Heel (to use a classical allusion) of the human will. Man is no longer subject to the demons. He is completely free to choose the good for himself. He is autonomous.

“I have set thee,” Burckhardt (via Mirandola) has the Creator say to Adam,

in the midst of the world that thou mayst the more easily behold and see all that is therein. I created thee a being neither heavenly nor earthly, neither mortal nor immortal only, that thou mightest be free to shape and to overcome thyself. Thou mayst sink into a beast, and be born anew to the divine likeness. . . . To thee alone is given a growth and a development depending on thine own free will.

Remarkable! This, readers of my blog will recall, had been the claim of Pelagius, the fourth-century heretic who claimed that human salvation is merely a matter of choosing freely to save oneself by embracing the Christian life. Against Pelagianism Saint Augustine had developed a doctrine of original sin that asserted man’s powerlessness in the face of evil and led to doctrines of predestination and universal human depravity. In the Christian east, by contrast, church fathers never embraced such a pessimistic view and spoke of human free participation in the life of God. But in the west, under the long and brilliant influence of Augustine, a series of pessimistic views about man came to prevail and led, over the centuries, to the desiccation of the human experience of paradise, of man’s participation in the kingdom of heaven.

The humanist breakthrough of the Renaissance, then, was not only a reaction against the anthropological pessimism of the medieval west, it was a kind of parallel to the optimistic anthropology of the Orthodox east. But this parallel was, tragically, blind. So little spiritual communion existed between eastern and western Christendom after nearly five centuries of division that Italian humanists showed little interest in the former. Plenty of western scholars were beginning to take an interest in “Greek learning”–most notably Petrarch himself–but theirs was not a theological interest. For them, the wisdom of the Greeks was the pagan Plato, not the Christian Palamas.

Whether medieval scholasticism’s tendency to “know about God rather than know him” was responsible, or something deeper in the fabric of western culture, the first humanists of the Italian Renaissance broke free of traditional Christian anthropology to join Mirandola in assigning to modern man a secular horizon for his fulfillment. Still driven instinctively (though perhaps unconciously) by traditional Christianity’s transformational imperative, but desiccated of the spiritual experience of paradise, he was now free to build a utopia.

Another fascinating read, Father John. Thank you.

“Still driven instinctively (though perhaps unconciously) by traditional Christianity’s transformational imperative …”

I’d tend to call that a very Vogelinian thought. This would be what Eric Vogelin, in that rather dense style of his, bristling with techicalities and neologisms, would have called “immanentizing the eschaton”.

And having thought that I just realised that I can’t recall a reference anywhere in Vogelin’s writings to the Greek Fathers. (There may be some, but if there are they can’t be prominent references.) Isn’t that interesting? This was a deeply serious man, one who, besides learning all the “important” modern and Ancient European languages, so that he could read philosophical and historical (and literary and imaginative) works in the original texts, even learnt Hebrew so as to read the Old Testament in the original language. Vogelin evidently thought that one needed to have read St. Augustine and the medieval Schoolmen (and the Bible) and not just Plato and Aristotle and then skip to Descartes and Hobbes and Hume, if one were to understand the West. This is a very much broader frame of reference than many thinkers have. But I wonder whether it ever occurred to him that maybe it’s important to know St. Athanasius, Gregory of Nanzianus, etc. as well.

Here’s another thought this threw up for me. I thought once again of C. S. Lewis’s “The Pilgrim’s Regress” — an astonishingly sparkling and interesting little allegory he wrote, and one of his first books I believe. One of the people John, the pilgrim, meets on his journey is Mr. Sensible. In political terms I suppose one might call him a Humean conservative, though he’s more to be seen in cultural than strictly political terms. (Some of Mr. Sensible’s comments and attitudes have, it seems to me, a distinctly (Michael) Oakeshottian flavour.) I believe it’s a mordant and accurate satire on that viewpoint. (Lewis dissects in this book, one-by-one, several positions people around him at the time as he was growing up must have been taking.) Anyway, one of the points Lewis has to make is that this “sensible” viewpoint, while it has some superficial charms and attractions, cannot satisfy or move anyone. This is symbolised in Mr. Sensible’s garden, which is a barren patch of dust in which Mr. Sensible’s servant, Drudge, raises radishes, which are all that will grow there. This kind of view, which has distant antecendents, in Lewis’s view in antiquity (the house Mr. Sensible is living in once belonged to Epicurus and later Montaigne) no longer works in a world which knows about what you just called “traditional Christianity’s transformational imperative” even if only “unconsiously”.

LikeLike

Pingback: On the Diminution of Angels | PARADISE AND UTOPIA