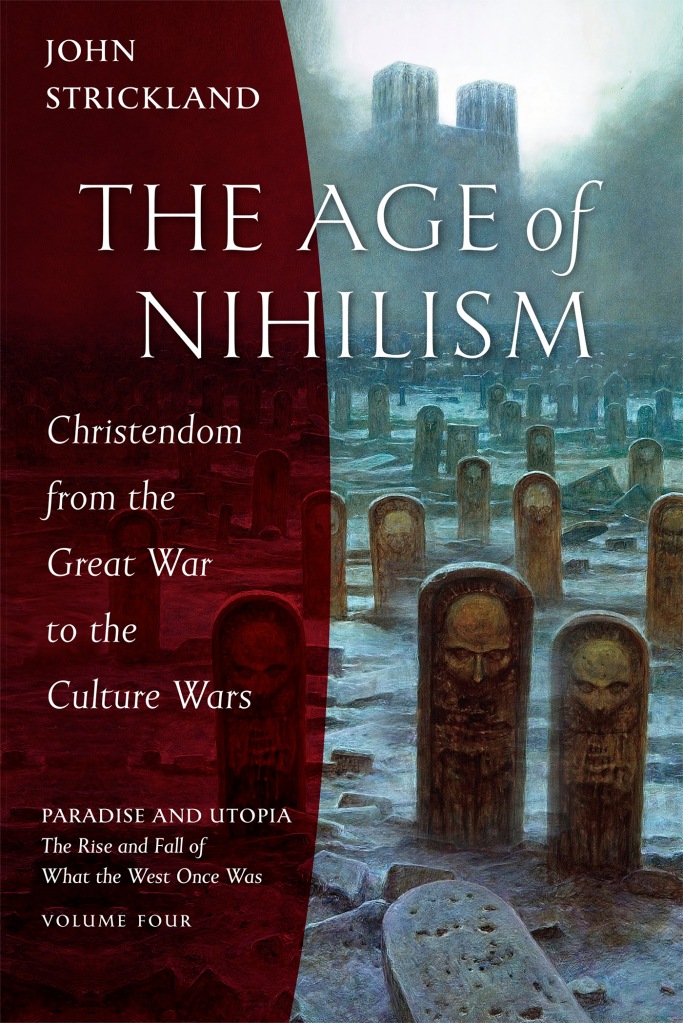

The fourth and final volume of Paradise and Utopia: The Rise and Fall of What the West Once Was, has recently been released by my publisher Ancient Faith Publishing.

The Age of Nihilism: Christendom from the Great War to the Culture Wars tells the story of how our civilization and its supporting culture, which once oriented the West toward a heavenly transformation of the world, reached a point of despair through secularization.

Continuing the narrative of The Age of Utopia: Christendom from the Renaissance to the Russian Revolution, the new book describes the “specter of nihilism” which appeared in the West at the end of the nineteenth century, the very moment secularism seemed triumphant. Part one reflects on the way nihilism became manifested in the music of Richard Wagner (composer of the famous “Wedding March” and “Ride of the Valkyries”), the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche (author of the claim that “God is dead”), the psychoanalysis of Sigmund Freud (with its degrading theory of the “Oedipus Complex”), and the painting of Pablo Picasso (which both documented and promoted the disintegration of the human image). It also presents the literature of Fyodor Dostoevsky (author of The Brothers Karamazov) as a powerful warning against secularization, though this warning was largely ignored until the specter of nihilism overwhelmed the West in the First World War.

Part two of the book tells the story of how three secular ideologies arose to exorcise the specter of nihilism, and how each ultimately failed to restore the linkage of heaven and earth once found in traditional Christianity. First Communism, then Nazism, and finally liberalism all tried once again to transform the world, but as ideologies they were counterfeits of true cosmological transcendence. Along the way, tens of millions of people in the West were killed through forced starvation (Communism), genocide (Nazism), and abortion (liberalism). Ideological world-building proved to be even more nihilistic than the secular humanism it tried to replace.

Part three reviews the failure of ideological world-building, focusing especially on liberal democracy in the West since the collapse of Communism (though an account of how the Soviet Union fell is also offered). As utopia became dystopia, existentialists, hippies, neopagans, and culture warriors all sought in vain to restore the dignity of humanity in a desecrated world. The narrative ends with the tragic outbreak of war between Russia and Ukraine in 2022.

A conclusion to the book series offers a reflection on the fundamental tragedy of the rise and fall of what the West once was: That after the Great Division of the eleventh century, our civilization and its supporting culture progressively lost the capacity of repentance and the virtue of humility on which a healthy culture depends. The great counterfeit of paradise, utopia, became inevitable when heaven was removed from earth and mankind directed toward a merely promethean transformation of the world.

The book can be purchased through Amazon here. The entire four-volume series can be purchased at a discount here.

The Temple of the Resurrection of Christ was only

The Temple of the Resurrection of Christ was only