My previous post of July 20, “Social Darwinists on Mrs. Gumdrop Street,” discussed the precipitous decline of compassion for the poor among the West’s nineteenth-century, post-Christian intellectuals. Ideological liberals like Herbert Spencer and Francis Galton exchanged “love thy neighbor” with “survival of the fittest.” However, in one of the great paradoxes of secularization, so did the period’s greatest socialist.

Continue readingCulture

Social Darwinists on Mrs. Gumdrop Street

In a previous post, I ruminated on an imaginary encounter between Charles Darwin–visionary of a secularized anthropology–and a working class widow begging for alms with her orphaned children on a cold and rainy street in central London. I named the woman and the street where she stood after Mrs. Gumdrop (Katerina Marmelodova), a character in Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment. That novel depicted the effects of an anthropology–or vision of humanity–in which people are no longer the image of God (imago Dei), the greatest standard by which a creature can be evaluated and the source of transcendent human dignity. Instead, people are beings–even animals–belonging to a genus-species named Homo sapiens. Measured biologically rather than theologically, man came to have a value only as great as his contribution to the natural order in which he lived. In a time of industrial competition and liberal individualism, this may have made those at the top of society great. But it made those at the bottom of society less than great, and even expendable.

Continue readingVolume Four Released

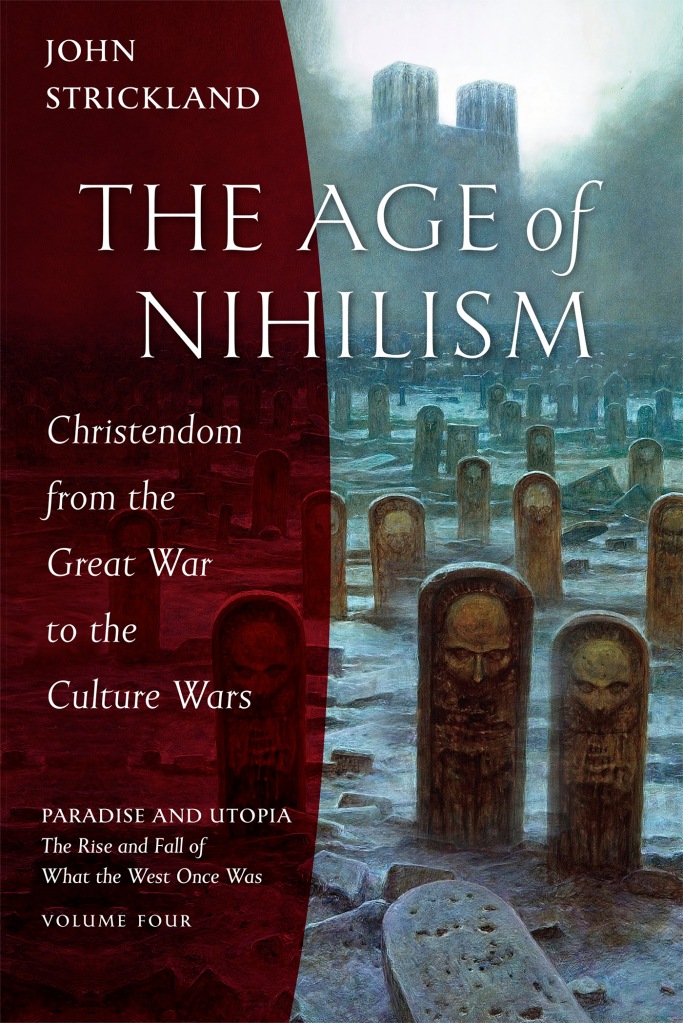

The fourth and final volume of Paradise and Utopia: The Rise and Fall of What the West Once Was, has recently been released by my publisher Ancient Faith Publishing.

The Age of Nihilism: Christendom from the Great War to the Culture Wars tells the story of how our civilization and its supporting culture, which once oriented the West toward a heavenly transformation of the world, reached a point of despair through secularization.

Continuing the narrative of The Age of Utopia: Christendom from the Renaissance to the Russian Revolution, the new book describes the “specter of nihilism” which appeared in the West at the end of the nineteenth century, the very moment secularism seemed triumphant. Part one reflects on the way nihilism became manifested in the music of Richard Wagner (composer of the famous “Wedding March” and “Ride of the Valkyries”), the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche (author of the claim that “God is dead”), the psychoanalysis of Sigmund Freud (with its degrading theory of the “Oedipus Complex”), and the painting of Pablo Picasso (which both documented and promoted the disintegration of the human image). It also presents the literature of Fyodor Dostoevsky (author of The Brothers Karamazov) as a powerful warning against secularization, though this warning was largely ignored until the specter of nihilism overwhelmed the West in the First World War.

Part two of the book tells the story of how three secular ideologies arose to exorcise the specter of nihilism, and how each ultimately failed to restore the linkage of heaven and earth once found in traditional Christianity. First Communism, then Nazism, and finally liberalism all tried once again to transform the world, but as ideologies they were counterfeits of true cosmological transcendence. Along the way, tens of millions of people in the West were killed through forced starvation (Communism), genocide (Nazism), and abortion (liberalism). Ideological world-building proved to be even more nihilistic than the secular humanism it tried to replace.

Part three reviews the failure of ideological world-building, focusing especially on liberal democracy in the West since the collapse of Communism (though an account of how the Soviet Union fell is also offered). As utopia became dystopia, existentialists, hippies, neopagans, and culture warriors all sought in vain to restore the dignity of humanity in a desecrated world. The narrative ends with the tragic outbreak of war between Russia and Ukraine in 2022.

A conclusion to the book series offers a reflection on the fundamental tragedy of the rise and fall of what the West once was: That after the Great Division of the eleventh century, our civilization and its supporting culture progressively lost the capacity of repentance and the virtue of humility on which a healthy culture depends. The great counterfeit of paradise, utopia, became inevitable when heaven was removed from earth and mankind directed toward a merely promethean transformation of the world.

The book can be purchased through Amazon here. The entire four-volume series can be purchased at a discount here.

When Charles Darwin Meets Mrs. Gumdrop

The Darwinian revolution in biology opened the way for a new conviction that man is an animal deserving the title Homo sapiens. The path was an exciting one, following the pioneering efforts of secularists like the eighteenth-century philosophes to establish a utopia in which man would, having vainly sought paradise for centuries, finally find fulfillment in a spiritually untransformed and godless cosmos. By the time Darwin died in 1882, man as imago Dei–the “image of God”–seemed irrecoverable.

Yet by discarding a divinely transcendent vision of man, the West stumbled into the greatest anthropological morass of its history.

Continue readingChristendom’s Anthropological Baseline

The claim that a human being is nothing more than a highly evolved animal, known collectively by the genus-species designation Homo sapiens, represented a turning point in the history of the West. Man, once dignified by the image and likeness of his Creator, became one with a spiritually untransformed world.

The claim did not come suddenly, of course. It was the outcome of centuries of reflections and assertions about the nature of man. It was a consequence of what in The Age of Utopia I call the “desecration of the world,” the progressive de-sanctification of a cosmos once filled with heavenly immanence. Beginning with the Renaissance, intellectuals proclaimed man’s autonomy in relationship to heaven. Instead of being the the image of a transcendent God, man was reconceived as Prometheus, after the mythical pagan figure symbolizing liberation from divinity. To this end, eighteenth-century secularists like Rousseau came to celebrate freedom from a distant “watchmaker god,” just as Voltaire envisioned, in his novel Candide, a humanity that could “cultivate the garden” of the earth without divine interference.

Man as Homo sapiens seemed to secure for the nineteenth century a hard-won autonomy. Yet in the end, the new anthropology not only subverted man’s dignity but the very autonomy it sought to secure. To understand this, it is necessary to consider what might be called Christendom’s anthropological baseline, the conviction that man is imago Dei and not Homo sapiens–nor even Prometheus.

Continue readingThe Old Christendom Enters a New Millennium

In two weeks, Orthodox Christians throughout what was once the Soviet Union will be celebrating the memory of the New Martyrs and Confessors of that land (those following the Western calendar in America and elsewhere celebrated the event yesterday). These people were killed for their faith between the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 and the collapse of Communism in 1991. Recognized as saints since 1982 by the Russian Orthodox Church outside of Russia, they were eventually canonized in Russia by the Patriarchate of Moscow in 2000. That event itself was a symbolical milestone in the history of Christendom, for it represented the restoration of traditional Christianity to a place of vitality within our culture. Continue reading

The Measure of All Insurrections

On October 25, 1917, an insurrection took place that must surely stand as one of the most momentous domestic attacks on government in history. Known as the Bolshevik Revolution, it set the standard of what an insurrection is and should by definition be.

A Holiday of Heavenly Immanence

Almost totally unknown in the West is the Orthodox Church’s commemoration of Christ’s baptism in the Jordan River. The holiday is one of twelve annual “great feasts,” and it occurs on January 6. It is known most commonly as Theophany (Greek for “divine appearance”), but also as Epiphany. That is the name for the feast among Roman Catholics and some Protestants. However, in the latter case the event commemorated is not the baptism of Christ but the arrival of the Magi in Bethlehem. The Orthodox do not discount the Magi (they are actually featured extensively in the hymnography of Christmas). But they attach far more significance to the baptism, seeing in the image of Christ standing in the waters of the Jordan the fulfillment of the Incarnation. What this holiday represents is the heavenly transformation of the cosmos.

There are several reasons for this. One is historical. In the early Church, the celebration of the Incarnation originally occurred on January 6, not December 25. Epiphany was a liturgical catch-all for a range of events associated with the great turning point in history of the world. Eventually, these were separated from one another to enhance the celebration. The Circumcision of Christ eight days after his birth (January 1); the Meeting of the Lord in the Temple forty days after (February 2); and the Annunciation to the Virgin Mary nine months prior (March 25) all filled in the calendar. Both East and West came to celebrate these events, but in the East January 6 remained the Incarnation’s central liturgical event.

Another reason is biblical. The scriptures present Christ’s appearance at the Jordan as the beginning of his public ministry, and not his birth. While some of their content speaks of the immediate impact of his birth (in addition to Matthew’s account of the Magi there is Luke’s account of the shepherds in the field), that event is in most ways obscured. The Magi themselves come and go without speaking to anyone but Herod. Once they do, the wicked king orders the Massacre of the Innocents in order to destroy Jesus. The short term outcome of the birth is in fact the flight into Egypt and continued hiding in Nazareth after the return. The baptism is the turning point from obscurity to evangelism. Matthew and Luke have almost nothing to say about the first thirty years of Jesus’s life. Mark, for his part, literally locates the “beginning of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God,” with the baptism. And all four Gospels make yet another important point. It was only at the baptism that the Holy Trinity was fully revealed as Son of God was immersed, God the Father bore witness to him, and God the Holy Spirit descended on him in the form of a dove.

A final reason for the primacy of the Theophany in Orthodox Church is cosmological, and this bears most directly on the holiday’s significance for the culture of Christendom. By immersing himself in the waters of the Jordan, Christ brought the Incarnation to its fulfillment. Having assimilated our humanity to his divinity, he submitted to the consequences of our brokenness, repentance. He was sinless and had no need of repentance, but by undergoing the baptism offered by John he joined the human race in its desperate turn to God for redemption. By doing so he sanctified the cosmos.

Water is the most elemental part of the cosmos and sustains its life. Just as the Son of God assumed a human body, by immersing himself in the waters of baptism he joined himself to a material creation which he himself brought into existence and in which he blessed the human race to live. The result was the transfiguration of the world, revealed in all of its glory on Mount Tabor later in his ministry.

The celebration of Theophany is therefore of great importance in revealing paradise to this world. This is why it has always been so solemnly kept as a holiday of heavenly immanence in the East. One of the Greek fathers, Sophronios of Jerusalem (d. 638), even composed a sacramental rite of water blessing for its celebration. Originally enacted at the Jordan River itself, the rite became standardized throughout the Orthodox Church and continues to be enacted at springs, rivers, lakes, and seas throughout the world today.

The most remarkable thing about this rite is its profoundly theological and poetic reflection on the union of heaven and earth. In addition to its statements about the participation of the material elements in the holy baptism of Christ, it unites the “today” of this world with the eternity of heaven. A brief excerpt from what is a long prayer provides a sense of this. “In the preceding feast we saw thee as a child,” the priest declares, referring to Christmas, “while in the present we behold thee full grown, our God made manifest, perfect God from perfect God.”

For today the time of the feast is at hand for us: the choir of saints assembles with us and angels join with men in keeping festival. Today the grace of the Holy Spirit in the form of a dove descended upon the waters. Today the Sun that never sets has risen and the world is filled with splendor by the light of the Lord. Today the moon shines upon the world with the brightness of its rays. Today the glittering stars make the inhabited earth fair with the radiance of their shining. Today the clouds drop down upon mankind the dew of righteousness from on high. Today the Uncreated of his own will accepts the laying on of hands from his own creature. Today the Prophet and Forerunner approaches the Master, but stands before him with trembling, seeing the condescension of God towards us. Today the waters of the Jordan are transformed into healing by the coming of the Lord. Today the whole creation is watered by mystical streams. Today the transgressions of men are washed away by the waters of the Jordan. Today paradise has been opened to men and the Sun of Righteousness shines down upon us.

A world so understood, in which the incarnate God is united with man, in which time is joined to eternity, and in which material things are transfigured by the presence of the immaterial–such a world is what Christendom has always sought to be.

A Tell-Tale of Two Cities

Twenty-twenty has been an interesting year for national monuments. In America, statues have been toppled on public squares everywhere, even as President Trump declares a heroic past beneath the stony visages of Mount Rushmore. In Russia, victory over Nazi Germany has been commemorated by the construction of a cathedral—one of the largest in the world—whose consecration brought President Putin alongside Patriarch Kirill. And in Turkey—once the heartland of Eastern Christendom, the majestic Hagia Sophia has now been designated by President Erdogan a national mosque. Continue reading

Russia’s Pearl Harbor Day

For most Americans, December 7, 1941 possesses a gravity and symbolism like few other dates in our nation’s history. It was the moment when America ceased to be free of the Second World War and became one of its most consequential combatants. It ended an era of isolation and catapulted us into a global superpower. And it was marked, of course, by a devastating suprise attack by the Japanese on our naval base at Pear Harbor.

But many Americans do not realize that Pearl Harbor Day has an equivalent in Russia, where entry into the war also occured involuntarily after a suprise attack by the enemy. In fact, the event marking the beginning of what Russians call the Great Patriotic War dwarfed America’s tragic losses, as did the body count when the war finally ended.

Half a year before our “day of infamy” (to quote President Roosevelt), the Soviet Union was forced into World War II by a suprise attack by Germany. On June 22, 1941, the entire weight of the Nazi war machine came crashing down on her western borders. Operation Barbarossa was the largest invasion in world history and was an even greater example of diplomatic infamy than Pearl Harbor. Without warning, the Germans smashed Soviet defenses to pieces along a border stretching two thousand miles from the Baltic Coast to the Black Sea. Within hours there was nothing left of the border. Within days, the Germans had destroyed or surrounded its reeling defenders. Within a month they had conquered a territory greater than Germany itself. And by December, they could see Moscow–six hundred miles from the border–in their field glasses. No suprise attack has ever been so overwhelmingly successful.

And yet it would ultimately collapse and lead to the ruin of Nazi Germany. The Red Army sustained unimaginably high losses but kept fighting. By the time Germany’s ally Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, in fact, the Russians had launched a counterattack that saved Moscow from capture. The road to Soviet victory was a long one, and would pass through even greater catastrophes like the heartbreaking siege of Leningrad (in which the Germans starved a million unarmed civilians to death) and the epic Battle of Stalingrad. After the two titans all but exhausted themselves in the tank battle of Kursk, the Red Army rose again to continue the struggle. There was simply no stopping it. By the summer of 1944 it had recovered nearly all of the territories lost to the Germans since Barbarossa. During the year that followed, it advanced inexorably to Berlin, where Hitler committed suicide. Soon after Germany finally surrendered.

Russia’s war against Nazi Germany has never been ignored in the West, but it has been neglected. Americans are far more familiar with D-Day than Stalingrad, with the Battle of the Bulge than the Battle of Kursk, and with Pearl Harbor than Operation Barbarossa. This is a natural expression of patriotism. However, it can sometimes have troubling consequences.

Recently, Russian president Vladimir Putin published an article in a Western journal criticizing the West’s sometimes myopic narrative about the Second World War. There was much that was inevitably political about the piece. But it did raise an important point: No long-term harmony between the United States and Russia is possible as long as the latter’s role in destroying twentieth-century fascism is ignored. Indeed, Putin’s article was provoked by a White House communique stating that in the fall of Berlin “America and Britain had victory over the Nazis.” In point of fact it was the Red Army that captured the German capital, but nowhere was this acknowledged in the brief Twitter statement. The suggestion was that it was a Western achievment.

This helps explain why in Russia today so much attention has been given to patriotism and the importance of national unity. At a time when America is experiencing divisions comprable the 1960s and national monuments are being thrown to the ground for their association with historical evils, Russia recently raised a monument in Moscow to her victory over Nazi Germany. It is not a statue, but a church.

In fact, it is one of the largest Orthodox churches in the world.  The Temple of the Resurrection of Christ was only completed within the past month and consecrated a week ago by Patriarch Kirill. And it was opened for public use today, June 22, the anniversary of Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union.

The Temple of the Resurrection of Christ was only completed within the past month and consecrated a week ago by Patriarch Kirill. And it was opened for public use today, June 22, the anniversary of Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union.

It is an example of a very different vision of modern culture than that which currently prevails in the secularistic European Union or America. Whether Russia will succeed in rebuilding her nation on a foundation that includes Christianity–as Ukraine likewise sought to do with the commemoration of Saint Volodymyr in Kiev last year–remains to be seen. But one thing is certain, having lost twenty-seven million lives along with other Soviet states during the Second World War (compared to America’s 420,000–an unquestionably heroic but far smaller number), she deserves the West’s respect.