The reorientation of modern Christendom toward an untransfigured world was, as I indicated in in another post, the central project of the Renaissance. This Renaissance project was inspired by the values of the classical pagan world, but it was also motivated more immediately by the desire to escape the increasingly pessimistic anthropology of medieval western Christendom. Humanists like Mirandola proclaimed a new humanity to their generation, one that possessed free will, one that enjoyed complete autonomy. This was the dream of the Renaissance, and it became over the centuries an inalienable feature of our modern culture. Continue reading

Orthodox Christianity

The Old Christendom Enters a New Millennium

In two weeks, Orthodox Christians throughout what was once the Soviet Union will be celebrating the memory of the New Martyrs and Confessors of that land (those following the Western calendar in America and elsewhere celebrated the event yesterday). These people were killed for their faith between the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 and the collapse of Communism in 1991. Recognized as saints since 1982 by the Russian Orthodox Church outside of Russia, they were eventually canonized in Russia by the Patriarchate of Moscow in 2000. That event itself was a symbolical milestone in the history of Christendom, for it represented the restoration of traditional Christianity to a place of vitality within our culture. Continue reading

A Holiday of Heavenly Immanence

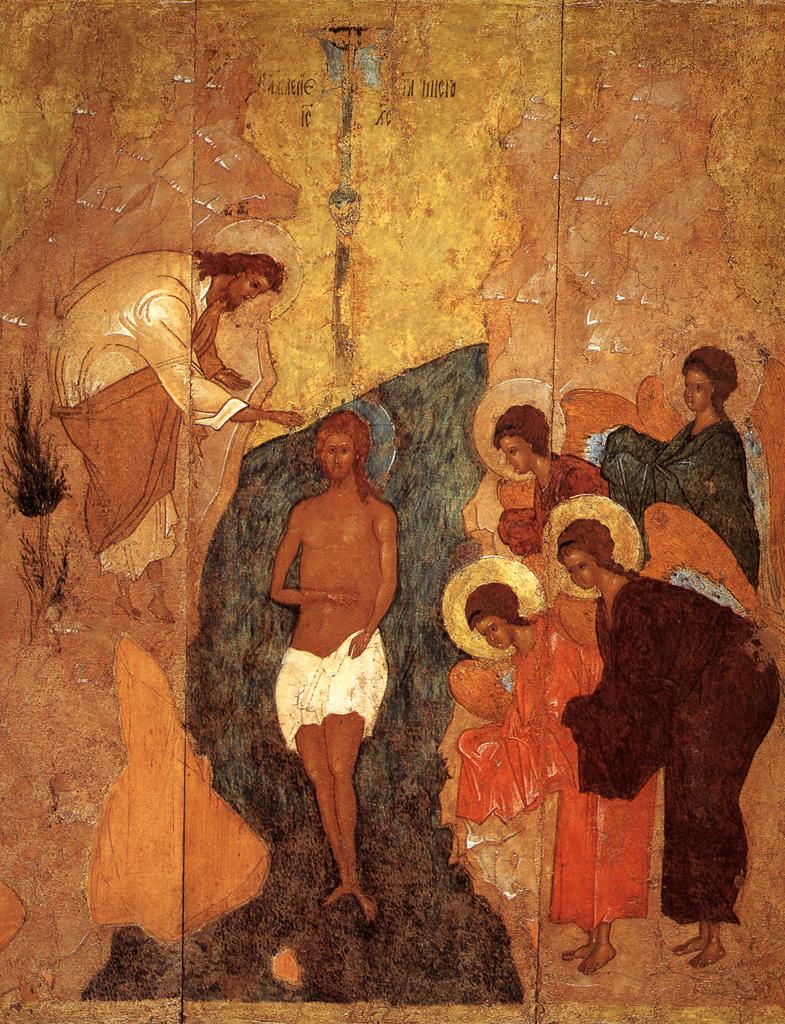

Almost totally unknown in the West is the Orthodox Church’s commemoration of Christ’s baptism in the Jordan River. The holiday is one of twelve annual “great feasts,” and it occurs on January 6. It is known most commonly as Theophany (Greek for “divine appearance”), but also as Epiphany. That is the name for the feast among Roman Catholics and some Protestants. However, in the latter case the event commemorated is not the baptism of Christ but the arrival of the Magi in Bethlehem. The Orthodox do not discount the Magi (they are actually featured extensively in the hymnography of Christmas). But they attach far more significance to the baptism, seeing in the image of Christ standing in the waters of the Jordan the fulfillment of the Incarnation. What this holiday represents is the heavenly transformation of the cosmos.

There are several reasons for this. One is historical. In the early Church, the celebration of the Incarnation originally occurred on January 6, not December 25. Epiphany was a liturgical catch-all for a range of events associated with the great turning point in history of the world. Eventually, these were separated from one another to enhance the celebration. The Circumcision of Christ eight days after his birth (January 1); the Meeting of the Lord in the Temple forty days after (February 2); and the Annunciation to the Virgin Mary nine months prior (March 25) all filled in the calendar. Both East and West came to celebrate these events, but in the East January 6 remained the Incarnation’s central liturgical event.

Another reason is biblical. The scriptures present Christ’s appearance at the Jordan as the beginning of his public ministry, and not his birth. While some of their content speaks of the immediate impact of his birth (in addition to Matthew’s account of the Magi there is Luke’s account of the shepherds in the field), that event is in most ways obscured. The Magi themselves come and go without speaking to anyone but Herod. Once they do, the wicked king orders the Massacre of the Innocents in order to destroy Jesus. The short term outcome of the birth is in fact the flight into Egypt and continued hiding in Nazareth after the return. The baptism is the turning point from obscurity to evangelism. Matthew and Luke have almost nothing to say about the first thirty years of Jesus’s life. Mark, for his part, literally locates the “beginning of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God,” with the baptism. And all four Gospels make yet another important point. It was only at the baptism that the Holy Trinity was fully revealed as Son of God was immersed, God the Father bore witness to him, and God the Holy Spirit descended on him in the form of a dove.

A final reason for the primacy of the Theophany in Orthodox Church is cosmological, and this bears most directly on the holiday’s significance for the culture of Christendom. By immersing himself in the waters of the Jordan, Christ brought the Incarnation to its fulfillment. Having assimilated our humanity to his divinity, he submitted to the consequences of our brokenness, repentance. He was sinless and had no need of repentance, but by undergoing the baptism offered by John he joined the human race in its desperate turn to God for redemption. By doing so he sanctified the cosmos.

Water is the most elemental part of the cosmos and sustains its life. Just as the Son of God assumed a human body, by immersing himself in the waters of baptism he joined himself to a material creation which he himself brought into existence and in which he blessed the human race to live. The result was the transfiguration of the world, revealed in all of its glory on Mount Tabor later in his ministry.

The celebration of Theophany is therefore of great importance in revealing paradise to this world. This is why it has always been so solemnly kept as a holiday of heavenly immanence in the East. One of the Greek fathers, Sophronios of Jerusalem (d. 638), even composed a sacramental rite of water blessing for its celebration. Originally enacted at the Jordan River itself, the rite became standardized throughout the Orthodox Church and continues to be enacted at springs, rivers, lakes, and seas throughout the world today.

The most remarkable thing about this rite is its profoundly theological and poetic reflection on the union of heaven and earth. In addition to its statements about the participation of the material elements in the holy baptism of Christ, it unites the “today” of this world with the eternity of heaven. A brief excerpt from what is a long prayer provides a sense of this. “In the preceding feast we saw thee as a child,” the priest declares, referring to Christmas, “while in the present we behold thee full grown, our God made manifest, perfect God from perfect God.”

For today the time of the feast is at hand for us: the choir of saints assembles with us and angels join with men in keeping festival. Today the grace of the Holy Spirit in the form of a dove descended upon the waters. Today the Sun that never sets has risen and the world is filled with splendor by the light of the Lord. Today the moon shines upon the world with the brightness of its rays. Today the glittering stars make the inhabited earth fair with the radiance of their shining. Today the clouds drop down upon mankind the dew of righteousness from on high. Today the Uncreated of his own will accepts the laying on of hands from his own creature. Today the Prophet and Forerunner approaches the Master, but stands before him with trembling, seeing the condescension of God towards us. Today the waters of the Jordan are transformed into healing by the coming of the Lord. Today the whole creation is watered by mystical streams. Today the transgressions of men are washed away by the waters of the Jordan. Today paradise has been opened to men and the Sun of Righteousness shines down upon us.

A world so understood, in which the incarnate God is united with man, in which time is joined to eternity, and in which material things are transfigured by the presence of the immaterial–such a world is what Christendom has always sought to be.

Approaching Wittenberg from the East

This year, the end of the present month of October will mark a full half-millennium since Martin Luther nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to the entrance doors of All Saints Church in Wittenberg, sparking the Protestant Reformation. Many have begun to commemorate this event throughout the world. For Protestants, it offers an opportunity to reflect on the many positive achievements of the Reformation. Many Roman Catholics and Roman Catholic publications have also joined in, noting the historically momentous and undeniably profound contribution of the Reformation upon modern Christianity. But where have the Orthodox been in this commemoration? Continue reading

The Secular Transformation of Western Art

The Renaissance was a reaction to medieval pessimism about the human condition. Petrarch, Mirandola, and other early humanists celebrated the dignity of man because western culture, despite deep roots in the anthropological optimism of traditional Christianity, had for centuries come to diminish the human experience of paradise in this world. Having explored this reaction in light of eastern Christendom, I would now like to turn to one of the most famous elements of the Renaissance, its art. Continue reading

An Eastern Perspective on the Western Renaissance

In the nineteenth century, the cultural historian Jacob Burckhardt famously characterized the Renaissance as a revival, after a full millennium, of the non-Christian values held by the ancient Greeks and Romans. This was not new, as contemporaries of the Renaissance such as Giorgio Vasari had themselves used “rebirth” as the metaphor of the culture of their time. Vasari (d. 1574) all but dismissed the value of the arts between the rise of a Christian culture in Europe after the conversion of Constantine and the rediscovery of classical art in his own time. But Burckhardt (d. 1897) canonized this interpretation for a modern audience. Henceforth the period of Christian art and culture that flowered for a thousand years was dismissed as the “middle ages” when traditional Christianity obscured the worldly potential of human greatness.

This view is no longer held in its purest form by historians, many of whom have today come to discover the riches of medieval art and culture. But like all great ideas it has cast a lasting shadow over our understanding of the past. Continue reading

The Desiccated Soil of Late-Medieval Western Christendom

The Christendom of the late-medieval west was a soil desiccated of the experience of paradise. Centuries of Roman Catholic piety had enriched this soil with faith in the kingdom of heaven, but not far below the surface there was an aridity that caused longing for a more immediate experience of it. Growing frustration was expressed in the period’s proliferation of mystics, and also in the life work of the man that would unintentionally inspire modern Europeans to depart from Christianity altogether, Francesco Petrarca, or Petrarch (d. 1374). Continue reading

The Pessimistic Cultural Atmosphere of Petrarch’s Christendom

By the late middle ages, western Christianity contained within it the distinctly pessimistic anthropology I described in my previous post. As I noted, this contrasted sharply with the anthropological vision of the east, recently defended by Gregory Palamas in the form of hesychasm. And when disasters struck in the west beginning with the fourteenth century, this pessimism was exposed and began to assume an even greater force. The Black Death in the middle of that century killed more than half of the population of western Europe. The Hundred Years War, by the time it was over in the middle of the fifteenth century, brought France and England to a point of exhaustion. Despair and the pessimism that accompanies it ran deep. Continue reading

The Specter of Anthropological Pessimism

What historians call the late middle ages was a difficult period in the history of western Christendom. From about 1300 to about 1500, a series of horrible events occurred including the Black Death and the Hundred Years War.

Dying Victims of Black Death

As they did, they caused new features of western culture to appear. Or perhaps it is more accurate to say that these catastrophes acted as abrasives across the surface of an otherwise verdant Christian culture, exposing stones that had long remained buried beneath it.

One of these long buried stones was what can be called anthropological pessimism, a emphatically negative view of the human condition in this world. Continue reading

Why Hesychasm Mattered

In yesterday’s post I presented the movement in fourteenth-century eastern Christendom known as hesychasm as a sort of foil (or contrasting device) against the disaffection that was stirring at the time among western thinkers such as Petrarch. The necessary link in this case was Barlaam of Calabria, the theologian who lived temporarily in Byzantium but fell out with the hesychastic current there and ultimately returned to his native Italy. There he converted to Roman Catholicism. Serving as Greek tutor to the illustrious Petrarch, it is conceivable that his agnosticism about the possibility of man experiencing the immediate presence of God in this world (what I call “paradise”) was passed on to his pupil, soon to be known as the father of modern humanism.

And so, we not only have a moment when a new stage in the history of Christendom is discernable–what I called the symbolical birth of utopia–but also an opportunity to reflect on what was being “left behind” in the old stage, represented as it was by the east. By this time, the Roman Catholic west had pretty much committed itself to what, to the Orthodox at least, appeared to be significant innovations. These included papal ecclesiology, scholastic theology, and doctrinal development (resulting in what had come to be called purgatory). As such, the west represented what might be called a “new Christendom,” and I will be spending time in future posts addressing it. But here I would like to say a few words about the “old Christendom” of the Orthodox east, and the important place hesychasm played in it. For it was this movement that not only embodied traditional Christianity’s conviction about the presence of God in this world, but insulated the east from forces that would eventually lead western Christendom into disarray. Continue reading