The story of Christ the Savior Cathedral in Moscow is a remarkable one, and well known by many Orthodox Christians in our time. Like so many of the stories of the New Martryrdom, however, few Americans know about it.  One of the largest Orthodox churches in the world, it was originally built in the nineteenth century. But it was blown up on orders of Joseph Stalin in 1931, and became the site of a remarkable–and almost comic–effort by the Communists to establish a new, post-Christian culture. Rebuilt after the collapse of Communism, it is in some ways a monument to the resilience of Christianity in the modern world and of the durability of Christendom. Continue reading

One of the largest Orthodox churches in the world, it was originally built in the nineteenth century. But it was blown up on orders of Joseph Stalin in 1931, and became the site of a remarkable–and almost comic–effort by the Communists to establish a new, post-Christian culture. Rebuilt after the collapse of Communism, it is in some ways a monument to the resilience of Christianity in the modern world and of the durability of Christendom. Continue reading

Culture

“Who Will Destroy Whom?”

Political revolutions cost lives, and so can cultural ones. This is true when the agent of change is the government, and that government is totalitarian. It is even more true when the totalitarian government is wedded to an ideology such as Communism.

In recent posts I have introduced the Soviet cult of Lenin within the context of the Communist Party’s violent assault on Christians. The Communists could not avoid violence in general because it was built into the ideology they inherited from Karl Marx. I will speak elsewhere about Marx’s place in the history of Christendom, but here I want to emphasize the role of violence in Marxism’s vision of history. History could not move forward without it. And history had to move forward. In the nineteenth-century “age of progress,” absolute standards of good and evil, cultivated by centuries of Christianity’s influence, were exchanged for a relativistic morality of progress. That which brought it about was good, and that which hindered it was evil. Continue reading

The Fool Says . . .

One of the really remarkable things about the Soviet cult of Vladimir Lenin was its religious character. It is a reminder that strict atheism is rare, even in the modern world.

There is a Psalm verse that speaks of how unusual and even ridiculous atheism is: “The fool says in his heart, there is no god” (Psalm 14:1). The Communists were adherents to the philosophy of Karl Marx and therefore strict atheists. They were convinced religion is an “opiate of the masses” imposed by class oppressors upon the workers and that there is in reality no god whatsoever. The Soviet Union was the first government in world history that committed itself to atheism. And yet, it was also the first government in history to invent a new culture, or system of beliefs and values, that was pseudo-religious. This can be seen in several features of the Lenin cult. Continue reading

Vladimir Lenin and George Washington: Two Cults, Different Ideals

When Lenin died of a stroke in 1924 the Communist Party was eager to immortalize him. The cult of Lenin that resulted went further than all earlier efforts in the history of Christendom–Christian or post-Christian–to glorify departed leaders.

The case of the United States is an interesting contrast. On the one hand, there were undoubted similarities. The “apotheosis of George Washington” depicted on the interior of the Capitol dome in a capital city named after the first president drew upon the pagan Roman practice of deifying departed emperors (that is, literally declaring them to be gods).  Washington was also glorified by a political culture in the early American republic that sought to create an almost mystical sense of his ongoing presence, expressed later by innumerable sites scattered throughout the eastern United States claiming that “George Washington slept here.”

Washington was also glorified by a political culture in the early American republic that sought to create an almost mystical sense of his ongoing presence, expressed later by innumerable sites scattered throughout the eastern United States claiming that “George Washington slept here.”

The difference between the cult of Washington and that of Lenin, however, was not just that the one was committed to individual rights and the other to totalitarian dictatorship. What really made the difference was that while Washington showed relative indifference to traditional Christianity and seems to have favored its Enlightenment alternative of deism, Lenin was an atheist and intended to create a civilization of atheists. And it was this goal that colored the cultural revolution that gave rise to his posthumous cult. Continue reading

“Lenin Lives!”

It was one thing to kill Russia’s Christians, and another to destroy Russian Christendom.

In a certain sense, of course, the elimination of Christians would achieve this end. In addition to Orthodox lay people such as the New Martyr Daria (whose execution I recounted in my previous post), most of the clergy was killed off or consigned to places such as Solovetsky Monastery, which was converted to a kind of clerical death camp.

Of some fifty thousand parish priests in 1917, only about five thousand existed two decades later. The bishops faced even greater odds against survival.

Without a body of the faithful or the clergy to lead them, the Communists reasoned, Christendom would wither and disappear. But they could not wait for that. They had seized power in the name of an entirely new and post-Christian civilization and intended to usher in its supporting culture as quickly as possible. They were men in a hurry.

And so they launched a cultural revolution on several “fronts.” In this post I will introduce one of them: The notorious cult of Vladimir Lenin. Continue reading

The Face of a Typical New Martyr

There is no such thing as a typical Christian martyr, for each one is unique in his or her witness to God’s love for the world. At the same time, each martyr was a person living in the age to which God assigned him, and therefore was joined to and served to sanctify the world during that time.

Thanks to modern photography (and the bureaucratic efficiency of totalitarianism), we know what a lot of the Christians who were shot to death for their faith in the Soviet Union looked like.  Precisely, vividly, and even in some cases rather artistically. Continue reading

Precisely, vividly, and even in some cases rather artistically. Continue reading

Shooting Christians

Yesterday’s news of the killings at Umpqua College in Oregon included a detail that, if true, reminds us that even senseless acts of violence occur within a cultural context.

The murderer was reported to have asked his victims if they were Christians before shooting them in the head. Non-Christians and those that declined to answer were reported to have been shot in non-lethal areas of their bodies. There is no point in speculating about the motives of a psychopath, other than to observe that somewhere he acquired a conviction that Christians are a threat to the world in which he briefly sought to live. That “somewhere” is our post-Christian culture. Continue reading

Cultural Revolution

Before the culture wars of contemporary American Christendom, there were the cultural revolutions of Europe’s totalitarian regimes.

When Trotsky hurled his “dustbin of history” curse upon those who declined to follow Lenin and the Bolsheviks in establishing a socialist utopia in 1917 (see my previous post), he was not only excoriating political rivals. He was suggesting that the Russian Revolution was about more than politics. It was also about culture, that is, it was about the radical transformation of beliefs and values. Continue reading

How Was Paradise Manifested in Early Christendom?

I have defined Christendom as a civilization with a supporting culture that directs its members toward the transformation of the world around them.

A very long time ago, this core value was grounded in the traditional Christian experience of paradise. This experience, the very kingdom of heaven, was joined to life in the world. God was everywhere present within it. Having entered into the world and assimilated it to himself through the incarnation, he gave new life to it and this in turn inspired a totally new approach to it. Christians now saw every aspect of worldly existence in light of the kingdom of heaven, which, while not of this world, was nevertheless in this world through the presence of the Church.

As a result, family life was transformed from a means toward security, status, affection, or sexual gratification into a real encounter with God and a taste of salvation. More problematic was the state, which after Emperor Constantine’s conversion rolled back the blood sports of pagan Rome, but did little to eliminate slavery and continued to descend into savage cruelty in its irrepressible lust for power. I will write about these and other examples of early Christendom in due time.

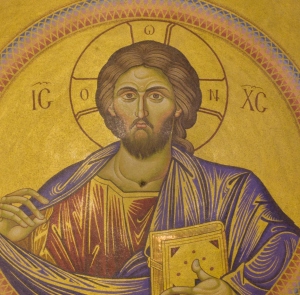

For now, though, let me direct your attention toward the way ancient Christian worship and the liturgical arts manifested paradise. Perhaps the best example of this is the central dome of a church building, which hovered over the inhabitants of Christendom (especially in the east) as the heavens do over one standing in the middle of a field in the darkness of the night. But instead of looking upward to behold the moon and stars, Christians beheld the face of God incarnate. An icon of Christ Pantocrator (which means “all-mighty” in Greek) was typically painted within the interior of the dome and gazed down majestically on those assembled.

To be sure, this was a breakthrough in the history of architecture and painting. But it was much more than that. It was a proclamation that “the kingdom of heaven has drawn near” to this world.

An interesting question to ask is, If a great percentage of the population of Christendom regularly stood within a church building and gazed upward into the face of an incarnate God who was visibly manifested in their midst, what effect would it have on their vision of the world around them?

A Triumph of Absurdity

While the Wagnerian suicide of Adolf Hitler in 1945 may have been the perfectly consistent end of a modern nihilist (see my previous post), the death of Albert Camus in 1960 was not.

True, this great French novelist and philosopher–a recipient of the Nobel Prize in 1957–was fascinated with nihilism, and even spent a good part of his early career as an exponent of it. Convinced with fellow existentialists Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir that God does not exist, he celebrated the absurdity of human action in the face of its resulting meaninglessness. An early work was The Myth of Sisyphus. For Camus the ancient figure of Sisyphus pushing a stone up a hill only to have it roll back down again–for all eternity–was the ultimate mythos of modern Christendom. For him, Sisyphus was a kind of post-Christian “hero of the absurd.”

Yet far more than his fellow existentialists, Camus was a dynamic thinker. He was never satisfied with his conclusions about the moral dilemmas of the modern west and progressively explored their root problems. This was the case with his fictional account of Nazi totalitarianism, a novel called The Plague. This beautiful book (one of my students once commented after reading it in our course that it made him “proud to be a human being”) took Camus beyond nihilism, back toward the central concerns of traditional Christianity.

Part of his inspiration was, interestingly, a lifelong attraction to Saint Augustine that contradicted his otherwise atheistic convictions. In the novel, evil is absurd, yes, and all-pervasive, but the protagonist’s response to it is not. A physician, he applies the cure of sacrificial love knowing that he can not completely annihilate the evil in this world, but knowing that he can prevent its triumph. Himself an atheist, the protagonist comes in spite of himself (and perhaps in spite of the author) to the remarkably similar conclusions of traditional Christianity. Indeed, some see Camus’s allegory of Nazism as a “proto-Christian” step in his intellectual development.

If so, his next work of fiction–and, alas, his last–went much further. The Fall is a very strange short book about a man who compulsively confesses his sins to a bartender. The man in question is a former judge, and an atheist. Or so he claims. Yet his preoccupation with a great sin he once committed reveals the weakness of his self-proclaimed nihilism, which he associates with Friedrich Nietzsche (who, it might be noted, was one of Hitler’s intellectual heroes). In the case of The Fall, Camus now takes his study of evil–what modern philosophers call theodicy–away from society and government and locates it . . . deep within the heart of the individual.

By this time in his career Camus had been visiting a Roman Catholic monastery off and on and was increasingly drawn to the values of traditional Christianity. It is significant that the sinner in the bar has the given name of Jean-Baptiste–John the Baptist, who once preached a “baptism of repentance.” His family name is also significant–Clamence, similar to “clemency,” or mercy and forgiveness. The problem is, he is an atheist. From whom does he need forgiveness?

Camus’s dynamic and honest struggle to confront the moral and philosophical problems of a post-Christian Christendom did not end with The Fall. Though self-consciously an atheist until the end, he continued to be drawn to the Christian anthropology of Saint Augustine.

Then, one day in 1960 he decided to accept the invitation of a friend to drive him to Paris by car. He would have preferred the train and had even bought himself a ticket. But nevertheless he agreed to drive. Along the way, the car went off the road and slammed into a tree.

Camus was killed instantly. At only forty six years of age, the restless philosopher who had traveled beyond modern nihilism into the heart of traditional Christianity might very well have gone further. It was a tragic end to a remarkable intellectual journey, and perhaps a truly absurd one as well. They even found the unused train ticket in his pocket.