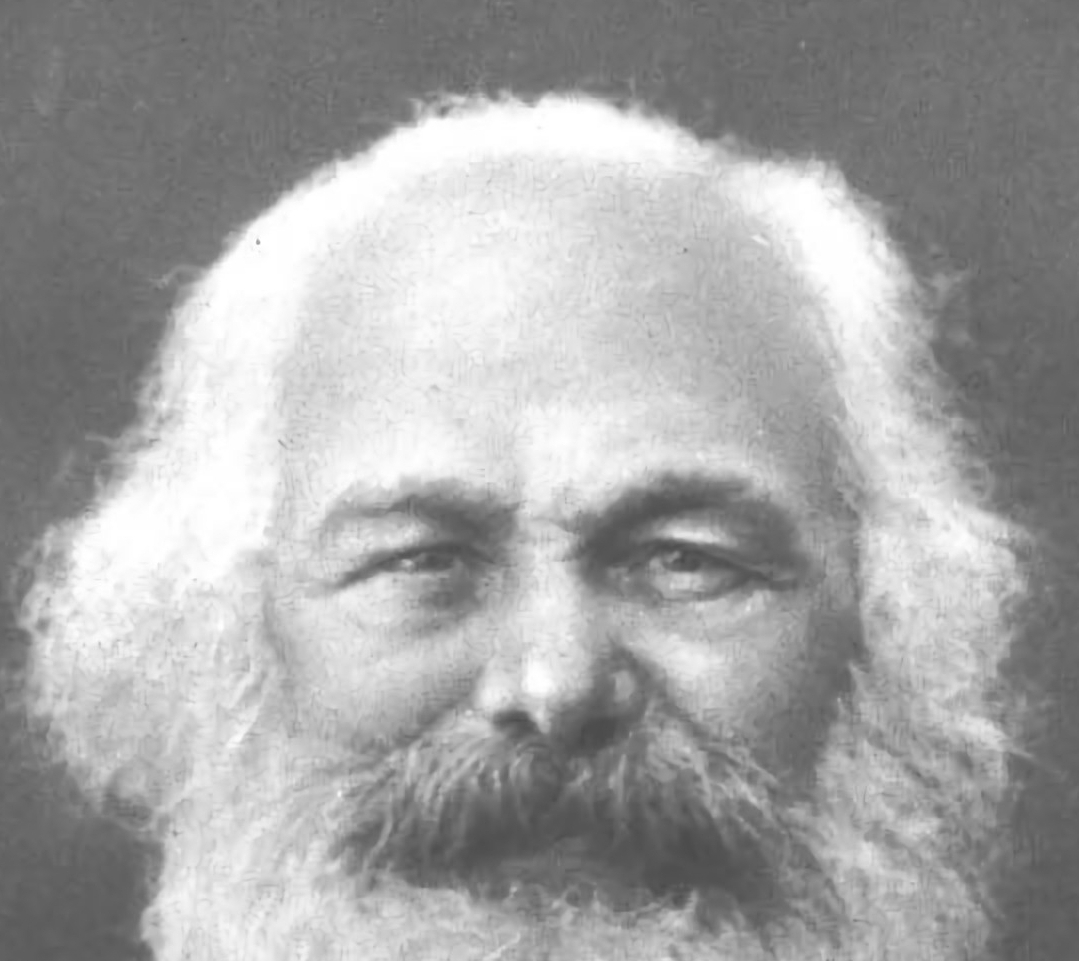

My previous post of July 20, “Social Darwinists on Mrs. Gumdrop Street,” discussed the precipitous decline of compassion for the poor among the West’s nineteenth-century, post-Christian intellectuals. Ideological liberals like Herbert Spencer and Francis Galton exchanged “love thy neighbor” with “survival of the fittest.” However, in one of the great paradoxes of secularization, so did the period’s greatest socialist.

Karl Marx (d. 1883) was an adherent of socialism, one of three ideologies that, as I have documented in The Age of Utopia, came to replace traditional Christian values during the nineteenth century and even served as a counterfeit of them. Unlike liberalism, socialism was concerned with the well-being of a working class that had suffered grave setbacks during the early phases of industrialization. For this reason, socialism can be seen as an ideological adversary to liberalism (concerned as the latter often was with the rights of middle-class individuals). Its concern with the interests of workers, who were often poor and exploited, suggested a continuation of the West’s traditional value of compassion. Indeed, with its call to revolution, socialism even appeared heroic.

Marx is known to many historians for advancing socialism from an “idealistic” ideology to a “scientific” one. With him, socialism moved from mere hopes about progress for the working class to one of scientific laws about it. This, certainly, is what the father of Communism claimed himself. Marx pored over empirical data about the economy in London’s British Museum Reading Room. Using his research, he erected a grand theory of economics and history that declared, in a language similar to Darwin’s, that natural laws not only govern human behavior but determine its outcome. Science, he claimed, proves that the future belongs to the industrial working class.

At the core of this theory was the Darwinian principle of natural selection. Marx wanted to dedicate his magnum opus, Das Kapital, to the great contemporary biologist. He agreed completely that individual members of a given species are locked in a relentless “struggle for existence” with one another, and that destruction and death pave the way of evolutionary progress. For Marx, though, social evolution depends on individuals of a given class organizing together to struggle against and annihilate their enemy class. As a result of industrialization, the two great class enemies were currently the proletariat and the capitalistic bourgeoise. Progress would come, Marx promised, when the former class overthrew and replaced the latter class in what he called the “proletarian revolution.”

To reach this turning point in history, however, very bad things had to continue to befall the working class. Marx introduced a principle of progress he called “immiseration.” According to it, the working class, in order to become sufficiently class-conscious and capable of the violence needed for the proletarian revolution, must, in the simplest terms, become ever more miserable. Conversely, if it experiences improvements through political reforms or economic prosperity, it will fail to play its “scientifically” assigned role in history.

And this is where Marx came to look very much like his ideological enemies Spencer and Galton. We can imagine Marx, displaced from his native Germany and living in rainy London, trudging down the street on which the working-class widow Mrs. Gumdrop stands with her freezing clutch of hungry children. Like other members of his class–that is, as a member of the bourgeoisie–Marx wears a top hat and suit. Upon reaching the corner where the woman stands, does he tip it toward her? Does he reach into his pocket for a coin to place in the beggar’s jar at her feet? The answer is, No.

Paradoxical as it is, Marx’s “dedication” to the working class entailed a principled refusal to help its individual members with monetary assistance. For doing so would only soften their rage. Their revolutionary tendencies would be reduced and progress would be impeded. Perhaps more resolutely even to the most stalwart Social Darwinist, Marx in our thought experiment walks past Mrs. Gumdrop with complete indifference to her personal suffering.

It is noteworthy, in fact, that Marx seems never to have had any real feelings of compassion for working-class persons during the course of his revolutionary life. For as a counterfeit of traditional Christianity, secular ideology tended to turn humanity into an abstraction. In Marx’s case, he never seems to have had a working-class friend, nor visited working-class families in their slums to ask how they were faring. He never seems to have had a real relationship with a worker.

There is one exception, however, and her name is Helene Demuth. She was a certifiable proletarian. And as such, she was hired by Marx to serve him as a maid. And it was with her that he betrayed his wife and conceived a child. Marx’s son, significantly, was immediately passed off to a working-class family and soon forgotten by the greatest socialist of post-Christian Christendom.

For her part, Mrs. Gumdrop was left behind on the street corner to await help from someone other than an intellectual bearing the values of secular ideology.